‘…Young peasant woman, married, moderately plump, infertile, with ovaries larger than normal, like doves’ eggs, lumpy, shiny and whitish’

With this expressive description in 1721, Italian scientist Antonio Vallisneri described for the first time the clinical and anatomopathological features of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).1 In 1935, PCOS was for the first time identified and investigated by Stein and Leventhal in a group of seven hirsute amenorrheic women based on typical ovarian morphology—fibrotic thickening of the tunica albuginea and outer cortex and multiple follicular cysts with distinct thecae.1 PCOS has since been one of the most controversial and explored areas of endocrinological gynaecology.

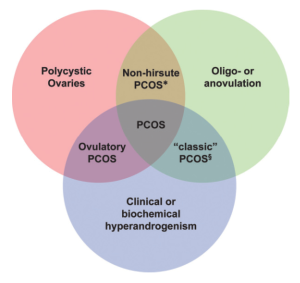

PCOS affects 4–20% of women of reproductive age worldwide. In India, nearly one in five (20%) women suffer from PCOS. As estimated by the World Health Organization, PCOS affected 116+ million women (3.4%) globally in 2021 alone.2 In 2003, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology along with the American Society for Reproductive Medicine conducted the first international consensus on the clinical criteria for PCOS at Rotterdam, Netherlands.2 As per the Rotterdam consensus, PCOS is defined by the presence of two of the three predetermined criteria, highlighting the range of clinical expressions within PCOS (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Rotterdam criteria for PCOS

The clinical presentation of PCOS includes the following:

- Ovulatory dysfunction (oligomenorrhea, irregular periods and/or anovulatory cycles)

- Male-pattern baldness

- Hirsutism

- Acne

- Fatigue

- Polycystic ovaries

- Weight gain

- Mood changes

- Low sex drive

- Trouble conceiving

Women with PCOS are at increased risk of type II diabetes mellitus, high cholesterol, high blood pressure and obesity, thus exhibiting insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. They are also at increased risk of certain cancers due to metabolic–endocrine abnormalities. An association between PCOS and cancer was first suggested 14 years after its original description. In 1949, Harold Speert, one of the world’s foremost historians of obstetrics and gynaecology, noted a recurrent presence of cystic ovaries in <40-year-old women with endometrial cancer (EC).3 Since then, several studies have supported this association.

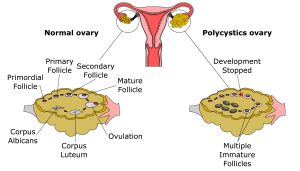

Figure 2: Development of PCOS

Endometrial cancer

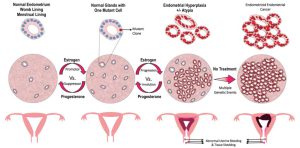

Women with PCOS are associated with three times greater risk of EC than healthy women. This is due to the prolonged exposure of the endometrium to the continuous unrestricted secretion of oestrogen caused by anovulation. The prolonged exposure induces endometrial hyperplasia, wherein the lining of the uterus becomes unusually thick. Endometrial hyperplasia is the potential precursor to adenocarcinoma. The risk factors of PCOS-associated EC include obesity, long-term exposure of unopposed oestrogen, nulliparity, infertility, hypertension and diabetes. Nearly 18% cases of adenomatous hyperplasia progress to cancer in the subsequent 2–10 years. Women with PCOS with a ≥3-month menstruation interval are at increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and EC.4

Possible biologic mechanisms of action

Long-term anovulation with continuous exposure to oestrogen unopposed by progesterone explains the increased risk of EC (an oestrogen-sensitive disease) in PCOS.5 Accordingly, intermenstrual cycle length correlates with the risk of endometrial hyperplasia. Endometrial responsiveness to progesterone is inherently different in PCOS. Secretory endometrium of some women with PCOS receiving ovulation induction or exogenous progesterone exhibits down-regulation of progesterone-regulated genes and up-regulation of cell proliferation genes. Hence, dysregulation of endometrial gene expression in PCOS accompanies progesterone resistance.5,6

Hyperandrogenism is one main component of all three clinical diagnostic criteria for PCOS. In 1998, Risch proposed that ovarian cancer (OC) is associated with factors related to androgen stimulation of ovarian cells.5 As demonstrated by animal studies, testosterone stimulates the growth of epithelial cells in the ovary.6 Androgens are crucial in OC development based on the following two hypotheses: 1) There is an increased risk of the borderline serous subtype of OC among women with PCOS. 2) Androgen receptors are relatively higher in serous borderline tumours compared to serous invasive.5 Moreover, androgen receptors and 5a-reductases are found in the human endometrium. Some women with PCOS exhibit the overexpression of endometrial androgen receptors, indicating disordered androgen action within the endometrium.6

Another common feature of PCOS is the hypersecretion of luteinizing hormone (LH), which acts as a regulator of endometrial growth, considering the ability of LH to promote the growth of EC cells in vitro. This is crucial as endometrial LH receptors are overexpressed in women with anovulatory PCOS with endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma, as they are in EC relative to tumour invasiveness.6

Nearly 70% women with PCOS develop disordered glucose-insulin homeostasis and insulin resistance. Hyperinsulinemia occurs due to distorted post-receptor signal transduction and decreases insulin-mediated glucose uptake without impacting steroidogenesis. Resultantly, excess insulin stimulates the activity of theca cell androgen and increases serum-free testosterone levels through reduced production of hepatic sex hormone-binding globulin, LH- and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I-stimulated androgen production and serum IGF-I bioactivity through suppressed IGF-binding protein production.6

PCOS is also associated with the dysregulation of glucose metabolic pathways in the endometrium. Treating cultured EC cells with IGF-I accelerates their growth, whereas exposing them to sera from metformin-treated women with PCOS diminishes cell growth and curbs inflammation and tumour invasion in signalling pathways. Hence, PCOS-related insulin resistance and EC share common mechanisms of metabolic dysfunction. The shared mechanisms likely include macrophage-secreted cytokine action on adipokines, which is concurrent with the ability of concomitant metformin treatment to reverse atypical endometrial hyperplasia in overweight women resistant to progestin therapy alone.6

PCOS affects body size through dietary intake and cravings as well as through its impact on metabolic factors linked to weight gain. Thus, BMI is a mediator and confounder of PCOS–cancer association, making it challenging to characterise a BMI-independent PCOS association.6

Figure 3: Development of Endometrial Cancer

Diagnosis of EC in PCOS

Along with medical history and general physical tests, EC is diagnosed as follows:

- Internal pelvic exam: It is performed to confirm the presence of lumps or modifications in the shape of the uterus.

- Pap test/ Pap smear: Cells are collected from the cervix and observed under microscope to check for abnormalities, which can be a potential cancer or increase the risk of it, and non-cancerous conditions, e.g., inflammation and infection.

- Endometrial biopsy: A small flexible tube inserted into the uterus collects a sample from endometrial tissue, which is viewed under a microscope to check for cancer or abnormal cell growth.

- Transvaginal ultrasound or ultrasonography: A transducer inserted inside the vagina produces sound waves that ricochet off the pelvic cavity organs. The echoes from the sound waves are captured by a computer to generate a sonogram.

- Dilation and curettage: This is a minor operation wherein the cervix is opened and the cervical canal and uterine lining are scraped using a spoon-shaped curette. The tissue is then subjected to microscopic examination.

In anovulatory women with PCOS and infertility, >7-mm endometrial thickness or >3-month intermenstrual interval is associated with endometrial hyperplasia.6

Ovarian Cancer

The risk of OC in women with anovulation has been a topic of debate and concerns in gynecologic oncology due to the extended use of ovulation-inducing drugs. Research suggests an association between OC and PCOS. The risk is particularly high in nulliparous women with early menarche and late menopause undergoing multiple ovulations. Women with PCOS fall in the low-risk group for developing OC due to their life-time reduced ovulation rate. However, certain ovulation-inducing treatments and multifollicular ovulation-inducing treatments theoretically create a technical imbalance to the risk of OC. Infertility alone increases the risk of borderline and invasive ovarian tumours. Another study linking clomiphene and OC suggests that the relative risk for OC for women with PCOS is 4.1 as compared to controls.4

Breast cancer

The link between PCOS and breast cancer (BC) remains debatable. Increased androgen and oestrogen levels increase the risk of oestrogen receptor-positive BC. The risk factors include genetic mutations, age, chemo and radiation therapies and family history. Hormonal contraceptives, a preferred treatment for PCOS symptoms, also increase the risk of BC.4 Circulating androgens participate in BC. In one pooled analysis, the risk of BC had increased with increasing testosterone levels in postmenopausal and premenopausal women.5

Majority of the clinical trials and research studies have investigated the correlation between PCOs and EC, whereas that between PCOS and OC/BC remains less explored.

Fighting PCOS!

- Diagnostics and treatment

Women with PCOS should undergo routine tests in a timely manner. These tests cover a broad range of profiles, including cholesterol, diabetic markers and hormone levels. In case of any PCOS-related symptoms, consult with a doctor so as not to delay the treatment. If untreated, disrupted hormone levels affect the whole body and increase the risk of life-threatening diseases, such as cancer.7 Regular testing assists in recognizing early signs of EC and initiating appropriate therapeutic measures as needed.

- Watch what you eat

Women with PCOS often have insulin resistance, for which a low-sugar low-fat diet is recommended, comprising vegetables, fruits, lean meats and high-fibre grains. Doctors also recommend foods with a low glycemic index, which allows slow and steady release of insulin, making energy utilisation easier than storing the food as fat.7

- Weight management

Nearly 50% women with PCOS exhibit overweightness/ obesity—risk factors of EC. Regular exercise helps reduce weight and testosterone concentration in the blood. Short-term weight loss restores fertility and ovulation and improves insulin resistance.7

- Mind–body exercises

Exercise also improves your mental health. PCOS is associated with an increased risk of mental and psychological disorders. Exercises that engage and elevate your mind and body are beneficial, e.g., meditation, yoga, Pilates and tai chi.7

References:

- Battaglia, C. (2003). The role of ultrasound and Doppler analysis in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 22(3), 225-232. https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/uog.228

- Bulsara, J., Patel, P., Soni, A., & Acharya, S. (2021). A review: Brief insight into Polycystic Ovarian syndrome. Endocrine and Metabolic Science, 3, 100085.. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S266639612100008X

- Speert H. Carcinoma of the endometrium in young women. Surg Gynecol Obstet (1949) 88:332–6.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18111780/

- Daniilidis, A., & Dinas, K. (2009). Long term health consequences of polycystic ovarian syndrome: a review analysis. Hippokratia, 13(2), 90.. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2683463/

- Harris, H. R., & Terry, K. L. (2016). Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk of endometrial, ovarian, and breast cancer: a systematic review. Fertil Res Pract, 2(1), 1-9. https://fertilityresearchandpractice.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40738-016-0029-2

- Dumesic, D. A., & Lobo, R. A. (2013). Cancer risk and PCOS. Steroids, 78(8), 782-785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2013.04.004.

- What to Know About Lifestyle Changes for PCOS. WebMD. June 08, 2021. Reviewed by Dan Brennan, MD. https://www.webmd.com/women/what-to-know-about-lifestyle-changes-for-pcos

Writer & Reviewer: Sharvari Indulkar and Dr Prachi Sinkar