Hepatitis is not just a viral infection affecting the liver, but an exigent pestilence with detrimental consequences on mankind. With five known types, namely hepatitis A, B, C, D and E, viral hepatitis leads to significant morbidity and claims millions of lives around the world annually. According to the World Health Organization, over 350 million people around the world are living with this life-threatening disease.1 Starting with hepatitis, let’s acquaint ourselves with the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and future directions of diagnostics.

What is Hepatitis?

Hippocrates was the first to describe benign epidemic jaundice in book ‘De Morbis Internis’ which resembled hepatitis A. The definition is accurate even today. Hepatitis is commonly defined as the inflammation of the liver. It might be due to a wide variety of causes, such as heavy alcohol consumption, autoimmunity, drugs or toxins; however, viral infection is the most frequent cause. Virally mediated liver inflammation, called viral hepatitis, is a significant burden. On the basis of severity, the condition can range between mild and self-limiting to a severe illness that requires liver transplantation. Based on the duration of the inflammation to the liver, hepatitis is categorised as acute inflammation (lasting for <6 months) or chronic inflammation (lasting for >6 months). Acute hepatitis is usually self-resolving but can cause fulminant liver failure. Contrastingly, chronic hepatitis can induce liver damage, fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and characteristics of portal hypertension that lead to significant morbidity and mortality.2

| Disease | Hepatitis A | Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | Hepatitis D | Hepatitis E |

| Causative Agent | Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) | Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) | Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) | Hepatitis D Virus (HDV) | Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) |

| Family | Picornaviridae | Hepadnaviridae | Flaviviridae | Deltaviridae | Hepeviridae |

| Genetic Material | RNA | DNA | RNA | RNA | RNA |

| Incubation Period | 2-6 weeks | 3-26 weeks | 2-33 weeks | 6-26 weeks | 2-6 weeks |

| Transmission | Ingestion, faecal-oral route | Parenteral | Parenteral | Parenteral, when co-infected with HBV | Ingestion |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, malaise, jaundice, anorexia, nausea, vomiting | Severe liver damage, chronic disease occurs | Same as HBV, more chronic | Severe liver damage, high mortality rate | Pregnant women may be at high risk and show mortality, not chronic disease |

Table 1: Viral Hepatitis At a Glance

Aetiology & Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is considered a major public health issue. Chronic infection with HBV and HCV can cause liver damage.2,3

- Hepatitis A Virus

HAV, a spherical 27-nanometer particle, was first discovered by Feinstone in 1973. It is a non-enveloped single-stranded RNA virus and the only species from the Hepatovirus genus that infects humans.4 The global infection rate of HAV is considerably high, but only 1.5 million cases are reported annually. Generally, people with access to safe drinking water and stronger socioeconomic regions have very low cases of HAV infection with <50% of the population being endemic, whereas people without access to safe drinking water and low-income regions have high levels of HAV infection with >90% of the population being endemic. In highly endemic countries, HAV infection at an early age with asymptomatic exposure acquires lifelong immunity in children.

- Hepatitis B Virus

HBV is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the Hepadnaviridae family and has ten genotype variants (A-J). The intact HBV virion is called the ‘Dane particle’. The viral core of HBV consists of nucleocapsid, hepatitis B core antigen that surrounds the viral DNA and DNA polymerase. The nucleocapsid is coated with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), a viral surface polypeptide. The gene coding for core antigen also codes for hepatitis B envelope antigen. Nearly one-third of the global population has had an HBV infection and around 5% of them remain carriers, whereas about 25% of these carriers develop chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Variations in the genotype distribution and risk factors rely on common factors in high-risk populations like vertical transmission which is associated with an increased risk of chronic disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. History of blood transfusion, intravenous drug or paraphernalia use, contaminated piercing instruments, sexual intercourse with an infected person and organ transplantation from HBV-positive donors are all risk factors for HBV transmission.

- Hepatitis C Virus

HCV, an RNA virus, was first discovered in 1989. It belongs to the Flaviviridae family with one serotype, minimum six major genotypes and 80+ subtypes. The extensive genetic variability poses a major challenge in developing a vaccine for the prevention of HCV infection. Globally, the most prevalent cause of parenteral hepatitis is HCV. High-risk groups for HCV infection include people who need frequent blood transfusions and people who receive organs from infected donors. With the development of safer screening and viral elimination techniques for blood transfusion, transfusion-associated HCV incidence is decreasing.

- Hepatitis D Virus

HDV, a single-stranded RNA virus, was first described in 1977 by Rizzetto et al in Italy by direct immunofluorescence. It contains the hepatitis D antigen and has HBsAg as its envelope protein. There are 8 different HDV genotypes; however, HDV-1 is responsible for most cases in North America, Europe and the Middle East. It is assumed as a defective virus as HDV requires the existence of HBsAg for full expression and replication. HDV infection occurs in HBsAg-positive patients as a coinfection with HBV or as a superinfection in chronic HBV carriers. About 10.58% of HBV carriers were coinfected with HDV, which is two-fold higher than the previously estimated. Western and middle Africa, the Amazon Basin, eastern and Mediterranean Europe, the Middle East and parts of Asia are the areas with the highest HDV infection carriage.

- Hepatitis E Virus

HEV, a small single-stranded RNA virus, is considered one of the most common yet underdiagnosed aetiologies. As per the World Health Organization, approximately 20 million HEV infections are detected annually, of which 3.3 million lead to symptomatic cases of acute hepatitis.2 HEV has been associated with outbreaks of food and waterborne diseases and is common in developing countries with limited access to sanitation, clean water and hygiene.

Pathophysiology

A virus enters the host system either through the enteric system or blood. Irrespective of the entry, the virus eventually travels to the liver where it infects hepatocytes, replicates either by direct translation of RNA or via reverse transcription of DNA and sheds the virions. HAV transmits via faecal-oral route. The virus disseminates into the liver via the portal vein, after it traverses the mucosa of the small intestinal wall. In HBV-infected cases, after the virus uncoats, its DNA integrates into the host nucleus as a covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) that can persist indefinitely in the hepatocytes, explaining the reactivation possibility in chronic inactive disease. Reverse transcriptase aids in the assembly of new viral molecules from cccDNA that are released by exocytosis. HCV is transmitted percutaneously (needlestick injuries containing contaminated blood) or non-percutaneously (perinatal transmission, sexual intercourse, blood transfusions, organ transplantation, religious scarification, body piercings or tattoos). The host-derived factors facilitating HCV entry are:

- Scavenger receptor class B type I

- Occludin

- Claudin-I

- CD81

Hepatocyte injury can either be self-limited and acute or insidious and chronic. The mechanism of hepatocyte injury is mediated by the host immune response against viral antigens which are expressed by infected hepatocytes and not as much by the cytopathic effects of the virus itself. The progression to chronic infection, as observed with HBV and HCV, is associated with the attenuation of T-cells that are virus-specific. Research shows that exhaustion of these virus-specific T-cells leads to an inability to clear the viruses, thereby allowing them to dwell chronically in host hepatocytes.3,4

Evaluating & Monitoring Hepatitis

Baseline evaluation of patients suspected with viral hepatitis begins with a hepatic function panel. Severely affected patients might have elevated aminotransferases and bilirubin levels. Acute hepatitis patients typically show aminotransferase levels in thousands. Chronic hepatitis varies in presentation with aminotransferase levels. Often, the levels are elevated to 2-10 times of the upper normal. In most cases, alkaline phosphatase levels remain within the reference range; however, significantly elevated levels should be considered as biliary obstruction or liver abscess. The values of prothrombin time and international normalized ratio may appear prolonged in advanced liver disease. Leukopenia and thrombocytopenia might also be observed. Advanced liver disease patients suffering from easy bruising, variceal bleed or hemorrhoidal bleed may have anaemia with low haemoglobin and hematocrit levels. For patients suspected to have advanced liver disease, blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine tests might be necessitated to check for renal impairment. For patients with altered mental status, serum ammonia levels must be checked as these are usually elevated in hepatic encephalopathy.2

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and polymerase chain reaction are the technologies that aid in the diagnosis of acute and chronic viral hepatitis. Other specific tests for evaluating the viral hepatitis type include:

- Hepatitis A

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody against HAV is the standard test for diagnosing acute HAV infection as it disappears after a few months. The presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against HAV signifies past infection and most patients with IgG antibodies have lifelong immunity against HAV.2,3

- Hepatitis B

The first serum marker to appear in HBV-infected patients is HBsAg, whereas the first antibody is IgM antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen. However, the presence of HBsAg does not signify acute or chronic infection in the absence of symptoms. In symptomatic patients, the presence of HBsAg strongly suggests acute infection but does not rule out chronic infection with an acute superinfection by another hepatitis virus.2,3

The presence of HBsAg, IgM core antibody, envelope antigen and viral load indicate acute HBV infection. A ‘window period’ is the duration during which HBsAg disappears before IgG antibodies appear against HBsAg. The presence of HBV DNA, HBsAg for >6 months, IgG core antibody and absence of surface antibody are indicators of chronic HBV infection.2,3

- Hepatitis C

The presence of HCV RNA with/without IgM antibody signifies acute HCV infection, whereas chronic infection is suggested by the presence of HCV RNA and IgG antibodies. HCV RNA would become undetectable once the patient has cleared the infection.2,3

- Hepatitis D

The presence of antibodies signifies HDV infection, whereas viral load is used for detecting current infection.2,3

- Hepatitis E

The presence of HEV antigen, RNA viral load and IgM antibodies indicate acute HEV infection. The patient’s response to antiviral therapy is evaluated using RNA viral load. IgG antibodies against HEV confirm vaccine efficacy or natural protection.2,3

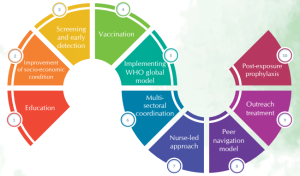

Figure 1: Action Plans for Controlling Viral Hepatitis

Join the Fight

The early detection of viral hepatitis depends on understanding the peculiar features of the five hepatitis viruses. Advances in the healthcare and diagnostics field have enabled timely and effective diagnosis as well as helped in establishing the multisystemic impact on the population. The advent of newer and improved therapies coupled with advanced diagnosis would promisingly aid in achieving control over this affliction a reality!

References

- World Health Organization. (2022, June 10). World Hepatitis Summit 2022 statement.https://www.who.int/news/item/10-06-2022-world-hepatitis-summit-2022-statement

- Mehta, P., & Reddivari, A. K. R. (2021). Hepatitis. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554549/

- Castaneda, D., Gonzalez, A. J., Alomari, M., Tandon, K., & Zervos, X. B. (2021). From hepatitis A to E: A critical review of viral hepatitis. World journal of gastroenterology, 27(16), 1691. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i16.1691

- Zarrin A, Akhondi H. (2022). Viral Hepatitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556029

Writer & Reviewer: Kayshu Grover & Dr Prachi Sinkar