Mukesh was never a fan of annual health check-ups. That changed the day he went for a medical check-up required for his job as a construction manager. His reports revealed that his prostate-specific antigen (PSA) had skyrocketed. An ultrasound and a biopsy confirmed his worst fears. A 54-year-old husband and father of two was diagnosed with stage 2 prostate cancer (PCA).

PCA is one of the most common cancers in men, accounting for about 15% of all cancer incidences worldwide and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in men. Most PCAs grow slowly and are relatively low-grade with low risk and limited aggressiveness. When suspected of PCA, what comes next is identifying the culprit, followed by assessing disease progression.1

The Culprits

Through efforts to understand the aetiology of PCA, it was found that they are multi-factorial and remain baffling with numerous modifiable/unmodifiable risk factors.1,2

- Age

Age is an established unmodifiable risk factor for PCA. It is found to be rare below the age of 40. The chances of developing PCA go up from 0.005% in <39-year-oldmen to 2.2% in 40-59-year-old men, and 13.7% in 60-70-year-old men. The probability of histological diagnosis of PCA is 50% higher in 70-80-year-old men, showing evidence of malignancy. Fortunately, low-grade histological diagnosis of PCA often follows a course without any significant risk of death.3

- Family History & Genetic Predisposition

PCA has an increased heritability. Men with brothers or fathers diagnosed with PCA have a four-fold risk of developing PCA, with a higher risk if a brother is diagnosed. The genetic risk factor increases with more relatives being affected. The risk of PCA is also high when families have breast cancer and PCA traits.3

- Smoking & Alcohol

Among the modifiable risk factors for PCA, smoking is associated with increased cancer incidence and mortality. In one meta-analytical study, the risk of PCA increased with increased smoking frequency. Ex-smokers had an increased risk of PCA, and heavy smokers had a 30% increased risk of PCA-related deaths. The association between alcohol consumption and PCA risk remains to be fully elucidated. However, a significant dose-response relationship between the two has been reported, where the risk increases with increasing alcohol intake compared to non-drinkers.3

- Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity and increased body mass index are associated with PCA. Increased adiposity increases PCA-related mortality risk. Possible reasons relating to PCA risk and obesity are insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), adipokines and sex hormones. Plasma adiponectin concentrations fall with increasing obesity, especially in men. Therefore, adiponectin can be used as a potential biomarker in PCA diagnosis.

A cluster of conditions including excess body fat with increased waist circumference, hyperglycemia, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia/ high triglycerides, is associated with metabolic syndrome, which increases the risk of colorectal and breast cancers. Metabolic syndrome is slightly associated with the incidence of PCA and greatly associated with aggressive disease spread and biochemical recurrence.3

- Physical Activity

Inverse relationship exists between the risk of progression and mortality from PCA and physical activity. A study of 2705 men with PCA revealed a 61% reduction in risk of PCA-specific mortality in men who did minimum 3 hours/week of vigorous exercise. However, there is no concrete evidence to prove that regular physical activity reduces the risk of developing PCA.3

- Diet & Nutrition

Numerous studies have investigated the association between PCA and our diet. Consumption of high-processed foods exhibit increased PCA risk, and conversely, intake of unprocessed/limited processed foods exhibit lower risk of PCA.3

- Medication

Metformin, an antidiabetic agent, is the cornerstone of type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment, but recent research has shed light on its anti-neoplastic properties, particularly in PCA patients. Metformin usage is reportedly associated with reduced PCA risk and progression. Various antineoplastic mechanisms of metformin involve pathways like adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activation and inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin activity and induction of apoptosis.3

- Hormones

Decades ago, studies described a close relationship between testosterone/androgens to prostate growth, which led to anti-androgen treatment as a cornerstone of metastatic PCA treatment. However, recently, there has been a paradigm shift in this understanding and application of testosterone to PCA risk, progression and survival. Considering intraprostatic androgen receptor sites are completely saturated/bound, anything above the baseline serum testosterone concentration plays no further role in stimulating prostate growth.1,3

- Infection, Inflammation and Chemokines

Chronic inflammation often results from exogenous stimuli like infections, chemicals, radiation, hormones and other noxious stimuli. Cancers/tumours can often be a subsequent chain of events related to chronic inflammation. The key feature of cancer-related inflammation is crowding leukocytes, production of cytokines and chemokines, subsequent disease progression, angiogenesis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration and metastasis. PCA is no different and numerous studies have investigated the role of cancer cell-produced chemokines and PCA-related chronic inflammation pathways.3

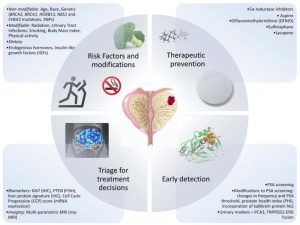

Figure 1: Prevention and Early Detection of Prostate Cancer

Paving way for Diagnosis

Early detection and treatment improves disease management and survival. Unfortunately, there aren’t any early warning signs for small bulk-localised PCA. The growing tumour does not push against anything to cause pain, so for many years, the disease may be silent. Hence, regular screening for PCA is important for all men, mainly >50-year olds.4

- Knowing the Genes

PCA seems to run in some families, suggesting that in some cases there is an inherited or genetic factor. Therefore, it is essential to determine the family history of PCA.

- Physical Examination

Physical examinations often include digital rectal exam (DRE). DRE test helps determine if the cancer is on only one or both sides of the prostate or if it has spread beyond the prostate to nearby tissues. Other areas of the body may also be examined.

- PSA blood test

PSA is a protein found in the prostate gland and produced by both normal and cancer cells. Although present majorly in semen, PSA is found in the blood in small amounts. This test is used mainly to screen for PCA in men without symptoms. It’s also one of the first tests performed in men with symptoms of PCA.

- Prostate biopsy

If PSA blood test, DRE or other test results suggest the presence of PCA, a biopsy is demanded to confirm the diagnosis. Small samples of the prostate are removed and looked at under a microscope. Core needle biopsy is the main method used to diagnose PCA.

- Staging and Grading

Once PCA is confirmed by biopsy, it’s important to learn the location (stage) and aggressiveness (grade) of the tumour.

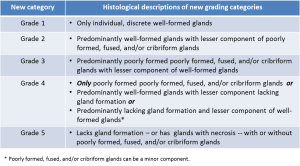

Figure 2: Histological Descriptions of New Grading Categories

- Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

Premalignant changes in the epithelium are referred to as prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). It is observed in over 70% of invasive PCA cases. It is seen much less frequently in normal prostates removed at necropsy. Around 40% non-cancerous prostates harbour PIN.3

- Genetic Testing

Some men with PCA are recommended to get tested for certain inherited gene changes. This includes men with suspected family cancer syndrome, such as BRCA gene mutation or Lynch syndrome, and men with PCA with high-risk features or metastatic growth.

- Transrectal ultrasound

Transrectal ultrasound is a procedure in which a small finger-wide probe is inserted in the rectum. This probe gives off sound waves that enter the prostate and create echoes. The probe then picks up the echoes, and the computer converts them into black-and-white image of the prostate.2

- Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging scans create detailed images of soft tissues in the body using radio waves and strong magnets. These scans can give doctors a very clear picture of the prostate and nearby areas. A contrast material called gadolinium may be injected into a vein before the scan to see details better.

- Computed Tomography scan

Computed tomography is less often required for newly diagnosed PCA, if the cancer is confined to the prostate. Still, it can help in analysing if PCA has spread into nearby lymph nodes. These scans can often tell if the cancer is growing into other organs or structures in the pelvis.4

- Lymph node biopsy

In a lymph node biopsy, also known as lymph node dissection or lymphadenectomy, one or more lymph nodes are removed to see if they have cancer cells. This is not done very often for PCA, but it is used to check if the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes.2

Beating PCA

Though it has one of the highest survival rates of any type of cancer, early accurate diagnosis, better therapies, understanding disease aggressiveness and progression, highlighting and addressing the key challenges and bridging the gap between unresolved questions in PCA can help improve the outcomes in successfully beating cancer.

References

- Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., Drescher, K., & Foy, D. (2015). Initial psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Questionnaire—Military version.Clinical psychology & psychotherapy, 22(1), 54-63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5911573/

- Cuzick, J., Thorat, M. A., Andriole, G., Brawley, O. W., Brown, P. H., Culig, Z., … & Wolk, A. (2014). Prevention and early detection of prostate cancer.The lancet oncology, 15(11), e484-e492. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4203149/

- Gann, P. H. (2002). Risk factors for prostate cancer.Reviews in urology, 4(Suppl 5), S3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1476014/

- Ng KL. The Etiology of Prostate Cancer. In: Bott SRJ, Ng KL, editors. Prostate Cancer [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2021 May 27. Chapter 2.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK571322/ doi: 10.36255/exonpublications.prostatecancer.etiology.2021 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK571322/#:~:text=The%20etiology%20of%20prostate%20cancer%20is%20multifactorial%20and%20remain%20quite,family%20history%2C%20and%20African%20ancestry.

Writer & Reviewer: Namitha Prabhu & Dr Sachin Patil